In our previous blog, we introduced the AI Application Journey—a framework showing how business context flows through five connected phases. Project Definition is the first and perhaps most critical phase, establishing the foundation that guides everything that follows.

Building a new AI business application is exciting. Being on the frontier of a new project, with new technology—often with lots of executive attention (and impatience). Everyone wants to start building—choosing models, selecting data, and perhaps trying out that new “Vibe Coding”—let the MAGIC happen! It’s so easy to fall into the trap of building the wrong thing quickly, due to a lack of clarity and understanding of the stakeholders’ wants and needs, the business objectives, requirements, scope, resources, and success criteria—in other words, a concrete project definition.

The foundation of a successful production deployment, and even an initial pilot deployment, lies in establishing a project definition that documents a shared understanding amongst stakeholders, both business and technical, about the objectives, requirements, resources, scope, and plan of the project. Perhaps most importantly, it lays out the success criteria for the project.

Of course, the project definition is not static—it’s a living document that evolves both as the work progresses and as the business needs themselves change. It serves as a communications vehicle, yet also as a tangible, integrated set of artifacts used throughout the project journey. It provides contextual information that can support both the development processes and the AI artifacts themselves.

Critical Questions for Project Definition

Understanding the Business Problem

What business problem are we really solving? This is the foundational question, yet teams often jump to the technical answer—”build a forecasting model”—rather than articulating the business problem: “regional managers can’t make confident quarterly projections.” Why does this problem matter now? What’s changed in the business? What business objectives does solving this support? Context Intelligence helps ground these questions in reality by connecting the problem to documented business capabilities and processes, showing how it relates to organizational structure, and linking it to existing business objectives and strategic initiatives. This prevents teams from solving problems in isolation or based on assumptions about what matters to the business.

Identifying Stakeholders and Their Needs

Who are the stakeholders, and what do they actually need? This goes beyond simply listing names. Who will use the AI, and what are their roles, responsibilities, and decision-making authority? Who owns the business processes being supported? Who controls the data and systems involved? What do different stakeholders need to consider this successful? Context Intelligence maps stakeholders to organizational structure and roles, identifies existing relationships and responsibilities, and surfaces potential conflicts or dependencies early. Without this, teams discover critical stakeholders late in the process or miss important political and organizational dynamics that determine success.

Defining Scope and Constraints

What’s in scope, and just as importantly, what’s explicitly out of scope? How much history is relevant – and available? Which regions, product lines, or organizations? What constraints exist around regulatory requirements, budget, timeline, or data access? Context Intelligence identifies which systems and data assets fall within scope, clarifies authorities and boundaries, and shows what’s already governed versus what needs new governance. This prevents unplanned scope creep on one hand and artificial limitations on the other. There is often a delicate negotiation in setting scope and constraints – its a key area where ongoing communications and review are needed to balance feasibility and desire – within a cost envelope.

Defining Success

What does success look like? This question deserves separate attention because it’s so often treated as an afterthought, yet it fundamentally shapes everything else. Success criteria aren’t just technical metrics like “accurate predictions”—they’re measurable business outcomes like “90% of regional managers using the system within six months” or “improve coverage and deployment of sales resources to match opportunities”. Context Intelligence links these success metrics to existing business measures, helping ensure the AI project aligns with how the business already tracks performance. And because business priorities evolve, these success criteria will likely evolve too—making them part of the living project definition. Success is not a one time event. Success must be sustainable over the life of a deployment – and set the stage for future successes as well.

Understanding Available Resources

What capabilities and systems are involved? Which business capabilities does this AI support or depend on? Which systems are relevant, what’s their current status and authority, and who owns them? What data exists and where? What technical infrastructure is available? What people, expertise, and processes can the project leverage? Context Intelligence systems can provide an inventory of relevant systems with their purposes and status, shows relationships between systems, data, and business capabilities, identifies authoritative sources versus archives, and maps data ownership and stewardship. This provides a starting point for the Data Readiness phase to assess the available resources with respect to defined requirements. (See my Colleague Mandy Chessell’s blog on Data Readiness at https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/data-readiness-ai-mandy-chessell-uyome)

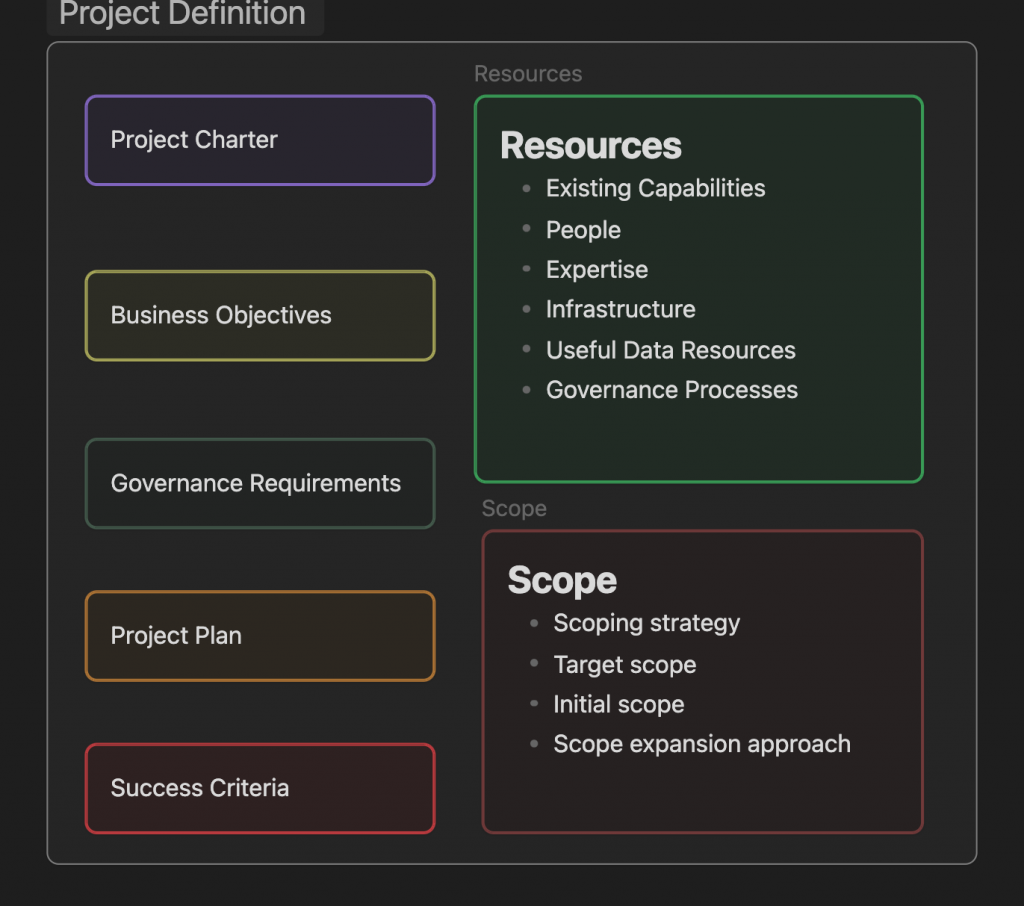

Components of Project Definition

While the following isn’t a formal project management methodology, it captures the essence of what’s needed in a project definition. As shown in the diagram, a comprehensive project definition includes:

- *Project Charter establishes the authority and framework for the project—who sponsors it, who leads it, and what commitments have been made.

- *Business Objectives articulate what the organization aims to achieve and why this project matters in that context.

- *Governance Requirements specify the policies, compliance needs, and oversight mechanisms that apply to this work.

- *Project Plan lays out the approach, timeline, and key milestones for executing the work.

- *Success Criteria define the measurable outcomes that determine whether the project has delivered value.

- *Resources encompass existing capabilities the project can leverage, people and their expertise, infrastructure, useful data resources, and governance processes already in place.

- *Scope includes the scoping strategy (how you’ll determine what’s in and out), target scope (the full vision), initial scope (what you’ll tackle first), and scope expansion approach (how you’ll grow from initial to target).

These components work together as an integrated whole. The business objectives inform success criteria. Resources and constraints shape realistic scope. Governance requirements influence both what you build and how you build it.

How Egeria Supports Project Definition

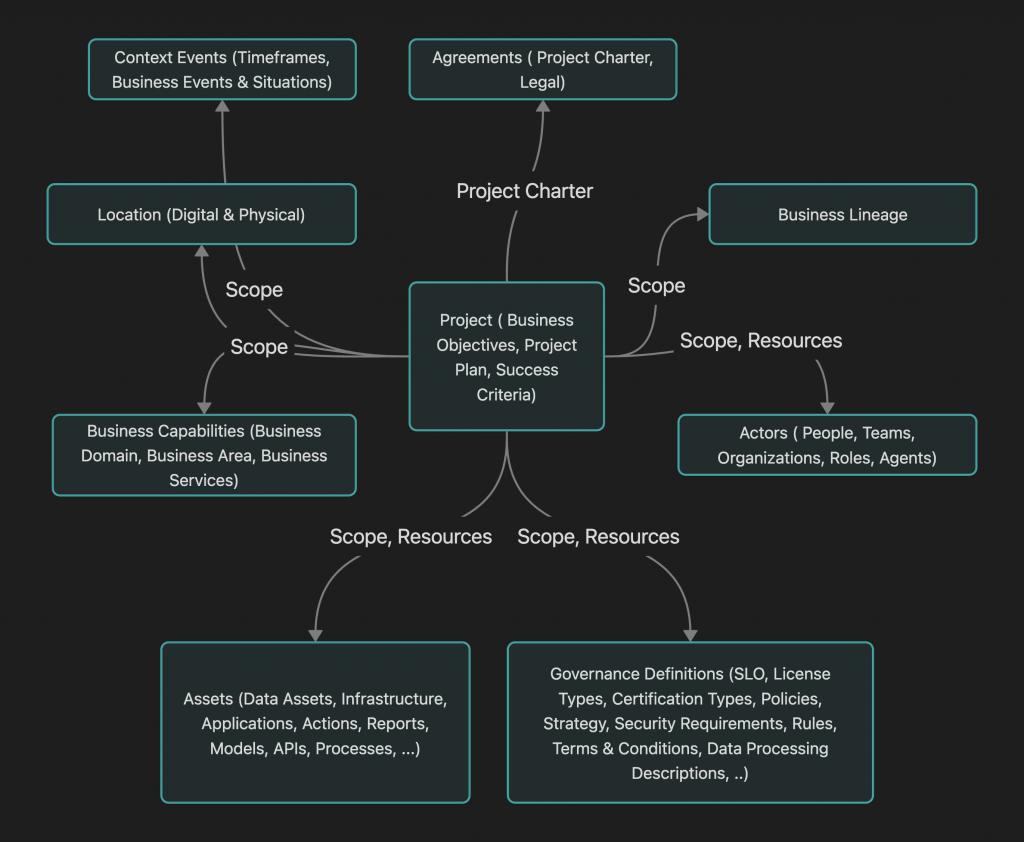

The open source Egeria Project enables Context Intelligence. Egeria allows us to not only document, but knit together the different aspects of project definition into a living infrastructure. Egeria’s open metadata types provide a rich framework for capturing, exchanging, and connecting project definition and context from different sources. Egeria incorporates a knowledge graph (or context graph) that enables us to link contextual elements together, allowing us to establish, find and use contextual information.

Project is a first class concept in Egeria. It includes business objectives, project plan, and success criteria as interconnected metadata. But the real power comes from how Egeria connects this central project definition to the broader organizational milieux.

Agreements, including both the project charter and any legal agreements such as data sharing agreements, establish the formal authority and commitments. Context Events capture the timeframes, business events, and situations that motivate and constrain the project. Business Lineage tracks how this project connects to broader business transformation efforts.

The project’s scope connects to multiple dimensions of organizational reality. Location metadata (both digital and physical) defines where the project operates. Business Capabilities link the project to specific business domains, areas, and services it supports or depends on. Actors—including people, teams, organizations, roles, and even automated agents (including AI Agents) —identify who’s involved and in what capacity.

Resources are equally rich. Assets include data assets, infrastructure, applications, actions, reports, models, APIs, and processes that the project leverages or creates. Governance Definitions encompass SLOs, license types, certification types, policies, security requirements, rules, terms and conditions, and data processing descriptions that apply to the project’s work.

All of these are connected through explicit relationships—scope relationships define what’s in and out, resource relationships identify what’s available and needed. This isn’t just documentation; it’s a queryable knowledge graph. You can ask, “Which databases are used for European sales reports?” or “What governance requirements apply to customer data in this country?” and get answers based on the metadata ecosystem that Egeria participates in.

Egeria’s approach is to facilitate the exchange of information among tools and data you have already deployed, to link this information together in a knowledge graph, and provide a consistent management and query mechanism to support its use. Egeria can survey existing data and systems to help you understand what is potentially relevant and then catalog and connect these sources— perhaps your CMDB, your reporting system, your governance tools—bringing scattered context together into coherent understanding. And as the project evolves, this metadata evolves with it, maintaining a living record of decisions and context that can serve not just the current project but future ones as well.

Sales Forecasting: Project Definition in Action

Let’s see how this plays out with our sales forecasting example. After the merger and restructuring, regional managers lacked a unified view of their forecasts across product lines. Different regions used different systems and different methods. The business objective was clear: establish a consistent forecasting approach across the organization. This would allow not just better financial planning but enable the utilization of sales teams across product lines and regions. Success was defined as 90% of regional managers actively using the system within six months and introduction of 2 new products to 3 different regions.

Context Intelligence revealed a complex stakeholder landscape. The obvious stakeholders—regional sales managers as primary users, the VP of Sales as sponsor—were just the beginning. The finance team consumed these forecasts for planning. IT owned the various regional systems. Data governance needed to ensure privacy and compliance. EU operations had different regulatory requirements than UK and North American — that teams hadn’t initially considered.

Scope definition became concrete through Context Intelligence. In scope: the current regional sales systems—two in North America, one in Europe and one in the UK. Explicitly out of scope: archived pre-merger systems and the product development forecasting process, which followed different patterns. Context Intelligence identified one system as archival before the team wasted time incorporating its outdated data. Authoritative systems and data were identified for each region, enabling the Data Readiness phase.

This foundation—captured in Egeria’s project metadata and connected to organizational context—guided every subsequent phase. When Data Readiness began, the team knew exactly which systems to assess and even which experts could provide insights into the existing systems. When development started, they understood which stakeholders needed which capabilities. When instrumentation was designed, success metrics were already defined and connected to business measures.

What Flows to Data Readiness

Project Definition establishes context that Data Readiness builds upon. The scope definition identifies which systems and data assets are relevant for assessment. Stakeholder needs translate into specific data requirements—European managers need data governed under GDPR, finance needs forecast data aggregated to specific reporting periods. Success criteria clarify what data quality and coverage is necessary—if 90% adoption is the goal, the data must support all major use cases. The authority understanding established in Project Definition tells Data Readiness which systems to prioritize as authoritative sources versus which are supplementary or archival. Constraints around privacy, compliance, and access identified early shape how data can be used.

Of course, this isn’t a one-time handoff—it’s living context. As Data Readiness reveals new insights about data quality or availability, the scope may need refinement. Stakeholder needs may evolve as teams understand what’s truly possible with available data. Context Intelligence maintains continuity through these changes, ensuring that refinements in one phase update the broader context rather than creating disconnected silos of knowledge.

Looking Ahead

With Project Definition complete, the team understands the business problem, stakeholders, success criteria, and scope. They know which systems and capabilities are relevant, which governance requirements apply, and what resources are available. Our next stop, in the AI Application Journey will be to jump into AI Application Development to explore some of the ways that Context Intelligence can augment Context Engineering in the development of AI systems. From this we will gain a better idea of the kinds of data and data preparation that will be needed to fuel the AI engines.

Really great post, thank you for sharing!